Adé Ben Salahuddin is a co-organizer of Black Birders Week 2022. He provided us with this reflection on the events of the week.

Barely seven days surpassing the start of Black Birders Week 2022, I was standing with science educator Dara Wilson inside the Smithsonians National Museum of African American History and Culture. Wed just finished recording a set of vital birding instructional materials for a Black Birders Week-themed page on the museums website. Over our heads, a set of screens cycled between black-and-white photographs of African American grassroots organizations and their members, both familiar and unsung. These were ordinary people who worked communities to protect and uplift each other in the squatter of discrimination, now memorialized.

It was for similar reasons of polity and encouragement that Black Birders Week was first organized, in 2020. The now annual, primarily online event was created by the Black AF in STEM Collective, a group of young Black biologists and nature enthusiasts. The goal was to bring greater representation to the world of birding in response to incidents like the one in Central Park in 2020 involving Black birder Christian Cooper. That wrangling highlighted the pervasive obstacles, dangers, plane hostility that Black people often squatter when were outdoors. As I mentioned in last years coverage, Black Birders Week has evolved from a joint reaction to a painful situation to a triumph of the people in our communities who have found joy, inspiration, and peace in birds and nature.

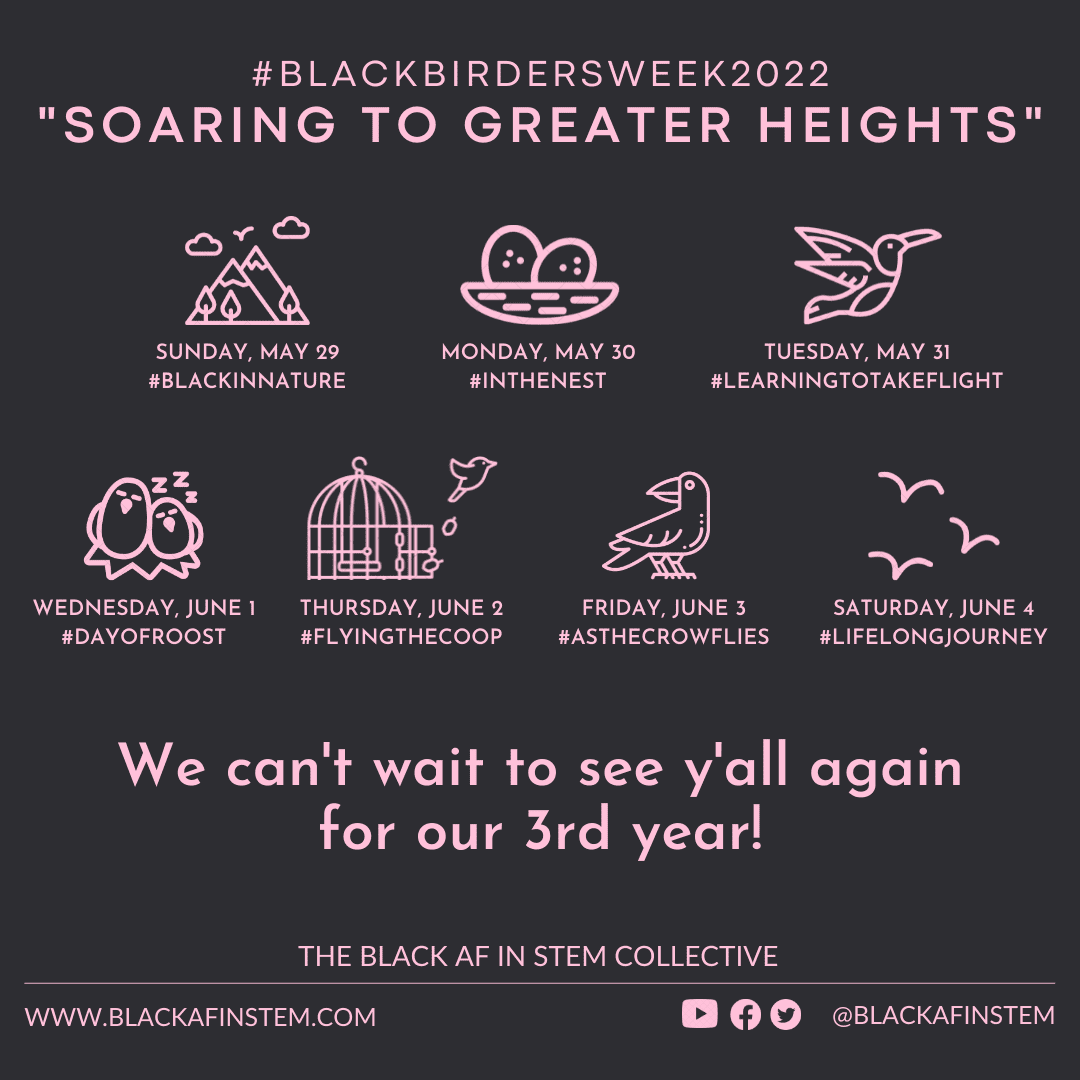

This years overarching theme, Soaring to Greater Heights, was a nod to the unfurled growth and expansion of Black Birders Week. Each day from May 29 to June 4, the week’s activities and online discussions explored a variegated theme emphasizing steps withal the birding journey. Participants and organizers unwrinkled reflected on their own experiences, painting a mosaic of birding through variegated cultures and perspectives wideness the African diaspora. For instance, the first day saw increasingly than 100 people from the U.S., Canada, the Caribbean, Europe, and Africa introducing themselves and showing off their birding experiences using the hashtag #BlackInNature.

Herpetologist and Week co-organizer Chelsea Connor kicked off a collaboration with the podcast BirdNote Daily with an episode well-nigh the Black Heron, highlighting the birds clever fishing strategy and its symbolism among local cultures wideness sub-Saharan Africa. The next two days, titled #InTheNest and #LearningToTakeFlight, featured a pair of webinars exploring the crucial role of mentorship and polity in creating new birders, from the points of view of both mentors and beginners (moderated by Deja Perkins and hosted by the Cornell Lab; archived here). Later that week on Thursdays #FlyingTheCoop, viewers were treated to the tropical sights and sounds of a virtual bird walk in the Bahamas surpassing tuning in for a presentation by Canadian teacher-turned-wildlife photographer Jason George and his journey with dyslexia.

A New Dimension: In-Person Events

Where this year’s events really moved vastitude the formula of previous years was in offering in-person events. With outdoor gatherings remaining a unscratched and popular way for people to physically interact, its only natural that folks are looking to hit the trails themselves and find communion in the nature virtually them. Environmental educator Nicole Jackson and urban ecologist Deja Perkins, both longtime Week co-organizers, hosted four bird walks (and a raptor demonstration) in their Ohio and North Carolina communities throughout the week, in wing to contributing to the virtual panels. Additional events included a nature walk hosted by Outdoor Afro of Southern California, and a bird walk in Pennsylvania led by environmental educator Brianna Amingwa.

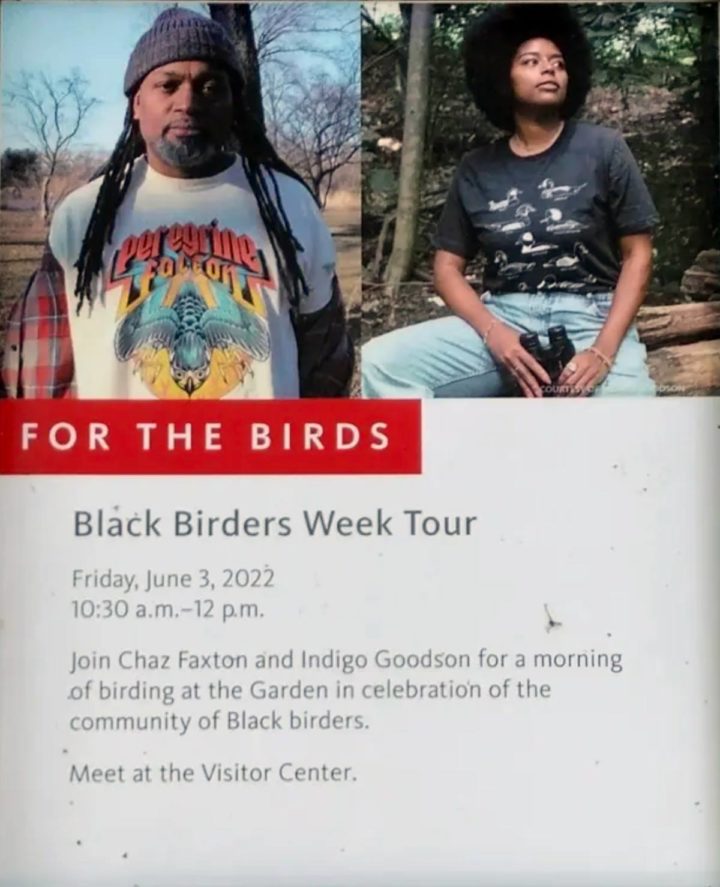

Over in New York City, I got to help develop and shepherd five bird walks through local parks and greenspaces. I began my Friday with a mid-morning venture through the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, co-led by Chaz Faxton and Indigo Goodson. We saw plenty of the typical municipality birds like House Sparrows, Blue Jays, and Northern Mockingbirdseven a Baltimore Oriolebut the biggest thrill came without the official walk had ended and well-nigh half of the 25 attendees lingered to squint out over a field. Suddenly, a Coopers Hawk dived in from directly overhead and snatched a fledgling European Starling wed been looking at, barely a dozen yards in front of us. (Pro-tip: whenever you think you want to leave is unchangingly when the surprises happen.)

Although birds were the focal point, I found it plane icreasingly memorable getting to meet other birders and enjoying moments together in the same physical space. Without taking a solitary afternoon stroll through nearby Prospect Park, I headed to Marsha P. Johnson State Park to meet up with Roslyn Rivas, a Bronx-based wildlife biologist and friend from higher who was leading a bird walk there that evening. This particular event, titled Birds and Brews, had been curated in partnership with the Brooklyn Brewery and was squarely aimed at a young sultana demographic. Jenna Marie Otero, an environmental education teammate at the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation & Historic Preservation, spearheaded the bird walk bar night collaboration. Nearly 20 people came, a racially and ethnically diverse group of scrutinizingly entirely first-time birders, with a handful of veterans among them. The walk itself was only well-nigh 35 minutesMarsha P. Johnson State Park is a relatively small spacebut the participants enjoyed highlights like a flock of Double-crested Cormorants sunning themselves in the East River.

Back at the Smithsonian, Dara and I were in the Explore More! Gallery helping museum attendees examine owl pellets and stray feathers under microscopes. A little Black girl, likely no older than 4, held a magnifying glass to her squatter as her mother helped her gently tease untied the tiny, slender wreck of an owl’s meal from the dry gray fluff encasing them.

I watched her examine and compare the variegated elements, using an illustrated sheet on the table in front of her to help tell a bird skull from a mouse leg. I beamed under my mask, elated that I could help bring this wits to this young anatomist in the making.

Across the room, an older Black man from New Orleans excitedly showed Dara videos of the Ospreys near his house, the trappy predators self-aggrandizing massive orange-scaled catches. “It’s good to know I’m not the only Black person who likes birds!” he tabbed to us as he left.

Standing in that space and looking out over the room, I took in the moment. Only a few months prior, I’d just started taking my new binoculars out to squint for birds at a small swimming near my house. Now, in one week, I’d been on seven variegated bird walks wideness multiple states, widow over a dozen new species to my eBird list, and most importantly made new connections with dozens of people. And as a homecoming surprise without all the work and travel was over, I found out that the community-building speciality of Black Birders Week had finally started taking root in my own Connecticut hometown while Id been away.

“It’s good to know I’m not the only Black person who likes birds!” the man at the Smithsonian had tabbed out to us.

Indeed it is, brother. Indeed it is.

Adé Ben-Salahuddin is a co-organizer of Black Birders Week 2022. He is an aspiring undergraduate-level evolutionary biologist and freelance science educator whose favorite birds are still all extinct (terror birds and moas). You can follow him on Twitter and YouTube for videos well-nigh prehistoric life, the people who study it, and how we talk well-nigh it.